10/11/2021 The Danger of Early Season Storms

Please don’t snow!... yet.

Come October, many skiers understandably get excited for winter and start praying for snow. But be careful of what you wish for! Early season snow in the mountains can often lead to a dangerous backcountry snowpack for most of the remaining season. While we appreciate the enthusiasm, here’s why it’s best to hold off. And if Mother Nature does provide an unfortunate early teaser, what you can do to stay safe.

The other F word

Early season storms in the Wasatch - and other non-maritime ranges - are rarely followed by continual snow despite the air feeling like it’s winter up high. So when a thin layer of snow is deposited and then met with frigid ambient temperatures, those dreaded facets are formed in short order. And if you remember from your avy 1 class, facets are angular grains of snow that have the consistency of kitty litter and refuse to bond to any type of snow. And since they’re slow to heal, they’re known as a persistent weak layer.

The simple explanation for the formation of facets is that due to a big temperature gradient - the difference between the ground (~32 degrees F) and below freezing cold air - water vapor quickly moves through the snow and changes the structure of the snow crystals to become very angular. Again, not good for avalanche stability.

So how does this affect the rest of the season?

Director of the Utah Avalanche Center, Mark Staples, explains it perfectly:

“Simply put - early season snow from the first handful of storms forms the foundation of the snowpack. It can be like building a house on a really weak foundation or a really strong foundation. In this analogy, when the snowpack gets deeper it's just like adding additional stories to the house. Eventually, the one with a weak foundation will collapse. When we get a collapse in the foundation of the snowpack, we get big avalanches.”

This is why it’s so important to monitor these early season storms.

“We need to know if the foundation of the snowpack will be weak or strong.”

Welp, it just snowed in October...

That said, if it does snow early, double down on your snow prayers ASAP! The more snow there is, the less quickly and easily facets can form. A fat snowpack has a much less extreme temperature gradient since there’s more snow insulating the ground from the air.

Here’s another option from guide and avalanche educator, John Lemnotis.

“A simple fix might actually be to pray for some rain! Let the rain eliminate all of the rotten snow on the ground and we get to start from scratch when mother nature is ready to remain cold and snowy. So, maybe think about turning that snow dance into a rain dance at certain times.”

In an ideal world, the season would start by snowing one foot a day for two weeks straight. And while we’re dreaming, let’s go ahead and ask for no wind whatsoever, dense snow the first week followed by increasingly fluffier snow, and then bluebird mornings to start each day.

But really, it snowed a foot last week with no more in the forecast. What now?

Here’s where it gets tricky. Once the facet fest gets going, it’s time to ditch the hopes and prayers in favor of homework and due diligence.

“With long durations between storms we will see the snow 'rot' and turn into facets depending on aspect and elevation,” Lemnotis says. “Knowing where in the mountains that old snow remains before another early season storm comes in can be really beneficial. With that knowledge you know where to look for weak layers that are now buried.”

This time of the year, early season snow has a decent chance of melting off entirely on south faces whereas it becomes highly unlikely to go away on north faces. East, west, and other aspects are wild cards. Elevation also plays a critical role since it’s obviously colder - and less likely to melt - the higher you go.

Remember, the new snow is NOT going to bond well with the facets.

Again, Staples adds:

“Doug Richmond, a long-time ski patroller and avalanche forecaster at Bridger Bowl used to always say “know there go there.” What he meant is that there’s just no substitute for going to a place and keeping an eye on the snow. You’ll be a lot smarter if you get out to some of your favorite drainages and areas in the early season. Combine your own observations with the avalanche forecast, and with other public observations, and you’ll have a really good sense of what’s going on with the snow.”

The facets are buried now, how do I know if they’re still dangerous?

First and foremost, check your local avalanche center forecast every morning and keep an eye on this layer. If it’s still in play, they will surely note it in the forecast. Another great option is to read the submitted observations. Backcountry users will often submit their own pit results. Combined, these can help give a bigger picture of the snowpack throughout an area.

Ultimately, Staples also encourages every user to dig their own pit as well.

“Since your life depends on what’s under your feet, it certainly helps to know what’s under them,” Staples says.

Make a habit of busting out that shovel and gathering information.

“Physically look at the facets. It's one thing to know they are lurking beneath your feet, but it's another thing to see and feel them. Seeing a stability test cause a column to jump into your lap can trigger other emotions that will also counter the lure of perfect powder.”

How to perform a proper pit test is beyond the scope of this article but if you need to learn or just brush up, there are many ways to do so! You can reread Staying Alive in Avalanche Terrain, take a class, check out a Mark Smiley online course, or hire a guide.

Eventually, the facets will heal, it’s just a matter of when and how. With any luck, winter will bring a lot of snow and bury those weak layers very deep. Once there’s enough snow, the snowpack will both bridge those layers from being triggered by your weight and also physically heal the facets.

At the very least, you can wait until spring to ski objectives in corn snow when the warm temperatures and strong sun have caused the snowpack to become uniform and isothermic.

Should I avoid the backcountry if there is a persistent weak layer?

Here’s where your homework will pay off. When thinking of stability in regards to those early season storms, you just have to avoid slopes that feature those facets or are connected to ones that do. Some seasons, the north face is very high danger while the south faces are game on. Or low elevation lines, even north faces, are good to go while anything higher is a roll of the dice.

And if everything is affected by those layers or other stability problems, you can still stay inspired in other ways. Around here, we lap groomers, focus on skimo racing, go on a road trip to somewhere with safer snow, get fat skis to make low angle meadow skipping even more fun on powder days, and challenge ourselves in other ways - perhaps work on getting a few coveted 10k days in or linking up traverses.

Eventually, the facets will heal and you’ll be able to hop on steeper terrain.

Key Takeaways:

-Early season snow followed by an extended period of dry and cold conditions leads to a dangerous snowpack foundation of facets that won’t bond well to added layers.

-Keep an eye on that snow and know where it still exists when the next storm comes around.

-Avoid steep slopes that feature those weak layers until you can know with certainty that they’re no longer influencing the stability of layers above them.

-Be patient!

Comments

10/13/2021

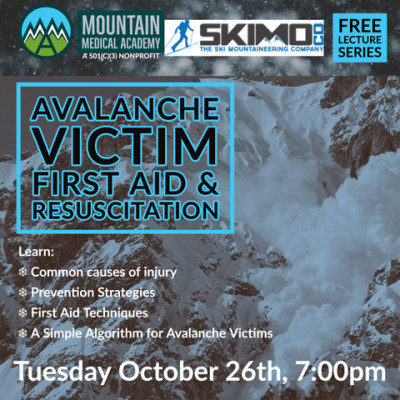

Event: Avalanche Victim First Aid